sexta-feira, 26 de junho de 2009

passeata de carro com Mulatu Astatke ao volante

É comprar, é ler o ípsilon de hoje, páginas 24 e 26. O amigo Mulatu e a Sasha Grey foram as pessoas mais bonitas do mundo desta minha semana.

quarta-feira, 24 de junho de 2009

Também ando para aqui encantado com o gosto da Sasha Grey (via Provas de Contacto). Sou um pavloviano irrepreensível no que toca a estas coisas.

(E curioso à brava com o último Soderbergh:

)

)

(E curioso à brava com o último Soderbergh:

)

)

há uma parte de mim, algures, que morre de saudades do Cintra...

"Mark Knopfler? Não duvido que seja um bom jogador mas temos o plantel fechado"

"Romário? Não, íamos era contratar o Rosário do Torreense, isso deve ser gaffe"

(...mas como não ter saudades deste homem?, um falador compulsivo, embora nem sempre inteligível. Um milagre ocasional.)

"Romário? Não, íamos era contratar o Rosário do Torreense, isso deve ser gaffe"

(...mas como não ter saudades deste homem?, um falador compulsivo, embora nem sempre inteligível. Um milagre ocasional.)

sábado, 20 de junho de 2009

quinta-feira, 18 de junho de 2009

segunda-feira, 15 de junho de 2009

The Good, the Bad and 'his Humphrey Bogart jacket open, his special smile'

It was a surreal day, an ominous day in Tehran yesterday, of censored newspapers and of soft words and threats against Mahmoud Ahmedinejad's political opponent, Mirhossein Mousavi. We didn't even know where Mousavi was – in custody or house arrest – nor whether a hundred of his election campaign workers had been arrested. It was a day heavy with plain-clothes policemen, blocked roads and jeering supporters of the government. No, there will not be another revolution in Iran. But this is not quite the democracy that Ahmedinejad promised.

True, we met Ahmedinejad the Good yesterday, preaching to us at an elaborately-staged press conference, talking of the noble, compassionate, honourable, smart people of Iran. But we also met Ahmedinejad the Bad, swearing to thousands of baying supporters that he would name the "corrupt" men who had stood against him in Friday's election.

I'm still not at all sure we met President Ahmedinejad, always supposing we believe in the 63.62 per cent of the votes that he claims he picked up. For what do you make of a man who five times refers to the presidential poll as a football match and then utters – in front of us all – in the softest of voices and with the gentlest and most chilling of smiles, a terrible warning to the mysteriously absent Mousavi. "After a football match, sometimes people feel their side should have won and they get into their car outside and drive through a red light and they get a ticket from a policeman. He didn't wait for the red light to change. I am not at all happy that someone ignores the red light." We all drew in our breath.

Less than two hours later, before the sweating thousands of his supporters in Val-y-Asr Square, we saw Ahmedinejad the Bad. "They are branding us as liars and corrupt," he screamed. "But they are themselves corrupt. I am going to use my position as president to name these people..." The crowd roared its approval. Of course they did. They all held Iranian flags or pictures of their pious leader amid heavenly clouds.

The day started badly with another of those dangerous, frighteningly brief statements from Tehran's loquacious police commander, Bahram Radan. "We have identified houses which are bases for the political mobs." This was the only reference the authorities would make about the outrageous street battles in which Radan's black-clothed cops beat Mousavi's supporters insensible on the streets of Tehran.

Then there was the front page of "Etemade Melli" – "National Trust" in English – which belongs to another of Ahmedinejad's enemies, Mehdi Karoubi. After the election results at the top of the front page – Mousavi officially won only 33.75 per cent of the votes and Karoubi 0.85 per cent – there was a caption: "Regarding the election results," it read, "Mehdi Karoubi and Mirhossein Mousavi made statements which we cannot publish in our newspaper." Beneath was a vast acre of white space. You could doodle on it. You could construct a crossword on it. You could draw a red light on it. But you couldn't read those statements.

And just to rub home the message – which we heard in various forms all day – a postage-stamp size photograph of Tehran's cops running down a street appeared at the top of page two with two worrying sentences. "The Public Security Police have delivered a statement, stating that any kind of gatherings, demonstrations or celebrations without a licence are forbidden. Any kind of gathering would be unlawful and the consequences will lie on the shoulders of the candidates and their campaign offices." We all knew what that meant; indeed, we approached Ahmedinejad's press conference with the absolute conviction that there would be more threats; there were, but they couldn't have been made in a kinder, more sinister way.

He sat before a vast spray of red and white roses, his back to a poster of a snow-tipped mountain, an Iranian banner floating in front, his Humphrey Bogart jacket open, his special smile – the UN smile, the CNN smile, the humble worker smile, the sportsman smile, the wisdom smile, we all know it – amid his whiskered features. There were prayers. And then came Imam Ahmedinejad. The Iranian people won the elections. It was their role to rule. "In countries where there was liberal democracy, the people are pushed out of the system and the professionals take over but in Iran, a democracy rules which is based on ethics."

It went on like this for quite a while. Iran loved all peoples. It would help all peoples. Iranians loved each other. They were unified. They would always stand together. "We are a noble people, we are smart people and the Iranian people believe in right and righteousness. The Iranian people hate lies and are satisfied with their lot... but we stand up to bullies and arrogance... the Iranian people will never be afraid of threats," he continued.

Readers will decode this as they wish. Clearly Ahmedinejad had read through Barack Obama's Cairo speech very carefully – indeed, he sometimes sounded grotesquely like the American president – and some of his "change" motifs fit rather well with the new US administration.

Bullying was in the past. We needed dialogue with all issues on the table. Post-World War Two political systems had proved anti-humanitarian. "The time when a handful of countries came together to decide the fate of a smaller country was over. It is finished."

It seemed endless. Democracy, ethics, human values, welfare, confidence, mutual respect, justice, fair play... From time to time it sounded like an updated version of Plato's Republic with the unwilling philosopher king behind the red and white roses.

But there was that infuriating refusal to deal with physical realities. When I asked Ahmedinejad the Good if he remembered the young Iranian woman dragged screaming to the gallows a few weeks ago, pleading with her mother by mobile phone to save her life seconds before her neck was broken by the rope, and whether he would guarantee that such a terrible event would never be repeated in the Islamic Republic, he set forth on an exegesis of the Iranian legal system. "I am myself against capital punishment," he replied. "I do not want to kill even an ant. But the Iranian judiciary is independent." And then he promised to talk to the judiciary about softening punishments and thought Iranian judges would benefit from "dialogue" with their opposite numbers in Europe and America. But the young woman so cruelly executed – for a murder she may not have committed – had disappeared from his response. She wasn't an ant. She had been in the hands of Ahmedinejad's noble, caring, compassionate, just Iran.

Nor was Mousavi an ant when CNN's Christiane Amanpour demanded Ahmedinejad the Good's guarantee for his life and those of his supporters. That's when we got the bit about the red light and all that it represented. Amanpour repeated the question. "Perhaps I missed something in the translation of your reply," she said sarcastically. "Perhaps you missed the translation that you didn't ask for a second question," Ahmedinejad snapped back. "No," said the imperishable Amanpour," this isn't a second question. I'm repeating the first one!"

Useless, of course, especially when the Iranian and Arab journalists arrived with their fawning questions, always preceded by congratulations for Ahmedinejad's real or imagined victory. In fact, the most frustrating thing about this performance was that he kept praising the massive turnout on Friday – perhaps more than 80 per cent – as his personal victory. But it wasn't the enthusiasm to vote that proved his presidency. It was the nature of how the result was calculated that enraged so many of Ahmedinejad the Good's noble Iranians.

But then, as they say, the mask slipped. Down amid the hot crowds on Val-y-Asr square – the scene of a huge 1979 Revolution massacre – Ahmedinejad the Bad was with us, screaming of his victory in confronting America.

"The enemy is furious because the Iranian nation is firm in its ideology... I will do my best to make the imperial powers and governments bow before you and bow before the nation of Iran."

His hand went up and down like a see-saw and the men and chadored women – some brought into Tehran by bus from the countryside, I noted from the registration plates – shouted "Ahmadi-, Ahmadi-, we are supporting you." And back came the vaunted boast: "America and other countries, you threaten Iran and you'll get your answer!" That's when he said he'd name his enemies.

So is it peace or war? It rather depends whether it's Ahmedinejad the Good or Ahmedinejad the Bad, I suppose.

For Mousavi's fate, watch this space.

(Robert Fisk)

True, we met Ahmedinejad the Good yesterday, preaching to us at an elaborately-staged press conference, talking of the noble, compassionate, honourable, smart people of Iran. But we also met Ahmedinejad the Bad, swearing to thousands of baying supporters that he would name the "corrupt" men who had stood against him in Friday's election.

I'm still not at all sure we met President Ahmedinejad, always supposing we believe in the 63.62 per cent of the votes that he claims he picked up. For what do you make of a man who five times refers to the presidential poll as a football match and then utters – in front of us all – in the softest of voices and with the gentlest and most chilling of smiles, a terrible warning to the mysteriously absent Mousavi. "After a football match, sometimes people feel their side should have won and they get into their car outside and drive through a red light and they get a ticket from a policeman. He didn't wait for the red light to change. I am not at all happy that someone ignores the red light." We all drew in our breath.

Less than two hours later, before the sweating thousands of his supporters in Val-y-Asr Square, we saw Ahmedinejad the Bad. "They are branding us as liars and corrupt," he screamed. "But they are themselves corrupt. I am going to use my position as president to name these people..." The crowd roared its approval. Of course they did. They all held Iranian flags or pictures of their pious leader amid heavenly clouds.

The day started badly with another of those dangerous, frighteningly brief statements from Tehran's loquacious police commander, Bahram Radan. "We have identified houses which are bases for the political mobs." This was the only reference the authorities would make about the outrageous street battles in which Radan's black-clothed cops beat Mousavi's supporters insensible on the streets of Tehran.

Then there was the front page of "Etemade Melli" – "National Trust" in English – which belongs to another of Ahmedinejad's enemies, Mehdi Karoubi. After the election results at the top of the front page – Mousavi officially won only 33.75 per cent of the votes and Karoubi 0.85 per cent – there was a caption: "Regarding the election results," it read, "Mehdi Karoubi and Mirhossein Mousavi made statements which we cannot publish in our newspaper." Beneath was a vast acre of white space. You could doodle on it. You could construct a crossword on it. You could draw a red light on it. But you couldn't read those statements.

And just to rub home the message – which we heard in various forms all day – a postage-stamp size photograph of Tehran's cops running down a street appeared at the top of page two with two worrying sentences. "The Public Security Police have delivered a statement, stating that any kind of gatherings, demonstrations or celebrations without a licence are forbidden. Any kind of gathering would be unlawful and the consequences will lie on the shoulders of the candidates and their campaign offices." We all knew what that meant; indeed, we approached Ahmedinejad's press conference with the absolute conviction that there would be more threats; there were, but they couldn't have been made in a kinder, more sinister way.

He sat before a vast spray of red and white roses, his back to a poster of a snow-tipped mountain, an Iranian banner floating in front, his Humphrey Bogart jacket open, his special smile – the UN smile, the CNN smile, the humble worker smile, the sportsman smile, the wisdom smile, we all know it – amid his whiskered features. There were prayers. And then came Imam Ahmedinejad. The Iranian people won the elections. It was their role to rule. "In countries where there was liberal democracy, the people are pushed out of the system and the professionals take over but in Iran, a democracy rules which is based on ethics."

It went on like this for quite a while. Iran loved all peoples. It would help all peoples. Iranians loved each other. They were unified. They would always stand together. "We are a noble people, we are smart people and the Iranian people believe in right and righteousness. The Iranian people hate lies and are satisfied with their lot... but we stand up to bullies and arrogance... the Iranian people will never be afraid of threats," he continued.

Readers will decode this as they wish. Clearly Ahmedinejad had read through Barack Obama's Cairo speech very carefully – indeed, he sometimes sounded grotesquely like the American president – and some of his "change" motifs fit rather well with the new US administration.

Bullying was in the past. We needed dialogue with all issues on the table. Post-World War Two political systems had proved anti-humanitarian. "The time when a handful of countries came together to decide the fate of a smaller country was over. It is finished."

It seemed endless. Democracy, ethics, human values, welfare, confidence, mutual respect, justice, fair play... From time to time it sounded like an updated version of Plato's Republic with the unwilling philosopher king behind the red and white roses.

But there was that infuriating refusal to deal with physical realities. When I asked Ahmedinejad the Good if he remembered the young Iranian woman dragged screaming to the gallows a few weeks ago, pleading with her mother by mobile phone to save her life seconds before her neck was broken by the rope, and whether he would guarantee that such a terrible event would never be repeated in the Islamic Republic, he set forth on an exegesis of the Iranian legal system. "I am myself against capital punishment," he replied. "I do not want to kill even an ant. But the Iranian judiciary is independent." And then he promised to talk to the judiciary about softening punishments and thought Iranian judges would benefit from "dialogue" with their opposite numbers in Europe and America. But the young woman so cruelly executed – for a murder she may not have committed – had disappeared from his response. She wasn't an ant. She had been in the hands of Ahmedinejad's noble, caring, compassionate, just Iran.

Nor was Mousavi an ant when CNN's Christiane Amanpour demanded Ahmedinejad the Good's guarantee for his life and those of his supporters. That's when we got the bit about the red light and all that it represented. Amanpour repeated the question. "Perhaps I missed something in the translation of your reply," she said sarcastically. "Perhaps you missed the translation that you didn't ask for a second question," Ahmedinejad snapped back. "No," said the imperishable Amanpour," this isn't a second question. I'm repeating the first one!"

Useless, of course, especially when the Iranian and Arab journalists arrived with their fawning questions, always preceded by congratulations for Ahmedinejad's real or imagined victory. In fact, the most frustrating thing about this performance was that he kept praising the massive turnout on Friday – perhaps more than 80 per cent – as his personal victory. But it wasn't the enthusiasm to vote that proved his presidency. It was the nature of how the result was calculated that enraged so many of Ahmedinejad the Good's noble Iranians.

But then, as they say, the mask slipped. Down amid the hot crowds on Val-y-Asr square – the scene of a huge 1979 Revolution massacre – Ahmedinejad the Bad was with us, screaming of his victory in confronting America.

"The enemy is furious because the Iranian nation is firm in its ideology... I will do my best to make the imperial powers and governments bow before you and bow before the nation of Iran."

His hand went up and down like a see-saw and the men and chadored women – some brought into Tehran by bus from the countryside, I noted from the registration plates – shouted "Ahmadi-, Ahmadi-, we are supporting you." And back came the vaunted boast: "America and other countries, you threaten Iran and you'll get your answer!" That's when he said he'd name his enemies.

So is it peace or war? It rather depends whether it's Ahmedinejad the Good or Ahmedinejad the Bad, I suppose.

For Mousavi's fate, watch this space.

(Robert Fisk)

quarta-feira, 10 de junho de 2009

"Se houver força suficiente entre os jovens que para que peguem no testemunho dos críticos italianos, que criem festivais, que façam trabalho de selecção, trabalho de estímulo, é possível que o entusiasmo deles seja recuperado. Quando as pessoas se dispersam, acaba-se tudo! Há uma velha fábula: um velho está a morrer e chama os filhos à beira da cama. Pede ao mais velho: 'Traz essas flechas; ata-as umas às outras e tenta parti-las'. O filho tenta mas não consegue. O velho diz: 'Parte-as uma a uma'. E então já as consegue partir. 'Se permanecerem unidos nada vos acontecerá'. Mas no contra-provérbio georgiano, o velho moribundo quer dar esta mesma lição clássica e diz ao filho: 'Vá, tenta lá partir as flechas'. O miúdo tenta e parte-as mesmo. Diz o pai: 'És um cretino e hás-de ser sempre um cretino!'.

Aqui está a resposta à vossa pergunta sobre o humor georgiano."

(Otar Iosseliani, Cinemateca Portuguesa)

Aqui está a resposta à vossa pergunta sobre o humor georgiano."

(Otar Iosseliani, Cinemateca Portuguesa)

sábado, 6 de junho de 2009

-Como era ela?

-Quem?

-Quem te pôs assim.

-O contrário de ti.

(citando de memória um diálogo de "Un conte de Noël", de Arnaud Desplechin)

(a propósito de Desplechin: "Falar de Desplechin como sendo alguém que leu demasiados livros e viu demasiados filmes sem compreender bem nenhum deles parece-me uma excelente descrição; é precisamente por isto que gosto dos filmes dele." - Animais Domésticos)

-Quem?

-Quem te pôs assim.

-O contrário de ti.

(citando de memória um diálogo de "Un conte de Noël", de Arnaud Desplechin)

(a propósito de Desplechin: "Falar de Desplechin como sendo alguém que leu demasiados livros e viu demasiados filmes sem compreender bem nenhum deles parece-me uma excelente descrição; é precisamente por isto que gosto dos filmes dele." - Animais Domésticos)

Subscrever:

Mensagens (Atom)

Arquivo do blogue

-

▼

2009

(93)

-

▼

junho

(15)

- passeata de carro com Mulatu Astatke ao volante

- Sem título

- Também ando para aqui encantado com o gosto da Sas...

- há uma parte de mim, algures, que morre de saudade...

- Joe Klein on Iran's Election (via roda livre)

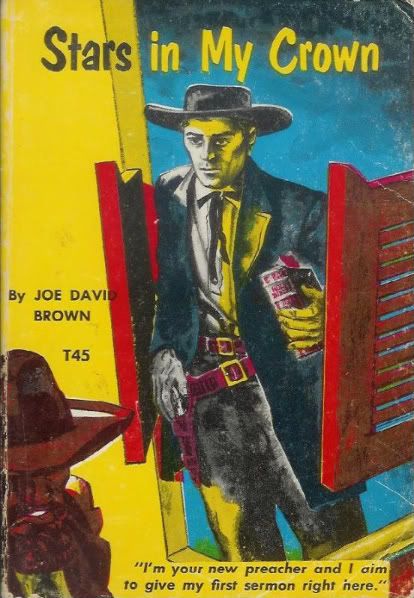

- Stars in My Crown, Jacques Tourneur, 50

- Sem título

- Broken Flowers

- The Good, the Bad and 'his Humphrey Bogart jacket ...

- Sem título

- "Se houver força suficiente entre os jovens que pa...

- E ainda não foi ontem que o vi. (Cartão daqui.)

- Sem título

- Sem título

- -Como era ela?-Quem?-Quem te pôs assim.-O contrári...

-

▼

junho

(15)

blogues

- A Causa Foi Modificada

- a divina desordem

- A montanha mágica

- A Origem das Espécies

- agrafo

- Ainda não começámos a pensar

- Amarcord

- ana de amsterdam

- Animais Domésticos

- Anotacões de um Cinéfilo

- ARCO Argentina ter plaatse

- As Aranhas

- as invasões bárbaras

- Auto-retrato

- avatares de um desejo

- Bibliotecário de Babel

- Bomba Inteligente

- Caustic Cover Critic

- chanatas

- Ciberescritas

- Complexidade e Contradição

- Complicadíssima Teia

- Da Literatura

- dias felizes

- Disco Duro

- Duelo ao Sol

- e deus criou a mulher

- Esse Cavalheiro

- Estado Civil

- ex-Ivan Nunes

- gravidade intermédia

- Horitzons inesperats

- If Charlie Parker Was a Gunslinger, There'd Be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats

- Intriga Internacional

- irmaolucia

- Joel Neto

- jugular

- Já Chovem Sapos

- lado “b” da minha mente

- Lei Seca

- Life and Opinions of Offely, Gentleman

- Léxico Familiar

- Margens de erro

- Menina Limão

- Mise en Abyme

- O Acossado

- O Anjo Exterminador

- O ente lectual

- O Falso Culpado

- O Inventor

- O Mundo pelos meus Olhos

- O Novo Selvagem

- o signo do dragão

- Ouriquense

- Pastoral Portuguesa

- Phantom Limb

- Poesia & Lda.

- Provas de Contacto

- Quetzal

- Ricardo Gross

- roda livre

- Sete Sombras

- Shakira Kurosawa

- sinusite crónica

- sound + vision

- State Of Art

- terapia metafísica

- the art of memory

- The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter

- umblogsobrekleist

- vida breve

- vidro duplo

- vontade indómita

- Voz do Deserto

«I always contradict myself»

Richard Burton em Bitter Victory, de Nicholas Ray.